West Virginia unsolved murders

http://www.charleyproject.org/cases/s/sodder_maurice.html

http://www.charleyproject.org/cases/s/sodder_martha.html

http://www.charleyproject.org/cases/s/sodder_louis.html

http://www.charleyproject.org/cases/s/sodder_jennie.html

http://www.charleyproject.org/cases/s/sodder_betty.

html http://www.doenetwork.org/

On Christmas Eve in 1945, the Sodders and nine of their ten children settled in for the evening. Maurice, and four of his siblings - Betty, Jennie, Louis and Martha Lee pleaded to be allowed to stay up and play with their new toys. Mrs. Sodder relented after the children promised to take care of their chores before coming to bed. Shortly after midnight Mrs. Sodder was awakened by the phone ringing. A female caller asked for a man whose name Mrs. Sodder didn't recognize. The caller gave a weird laugh before hanging up. Dismissing the call as a prank, Mrs. Sodder went to return back to bed but noticed the lights were still on, the shades weren’t drawn and the doors hadn’t been locked. Believing the children forgot to do these things before going to bed, she went back to sleep. She was awakened again by a noise on the roof that sounded "like a rubber ball." About a half-hour later, smoke began pouring into the bedroom. She yelled for her husband and children.

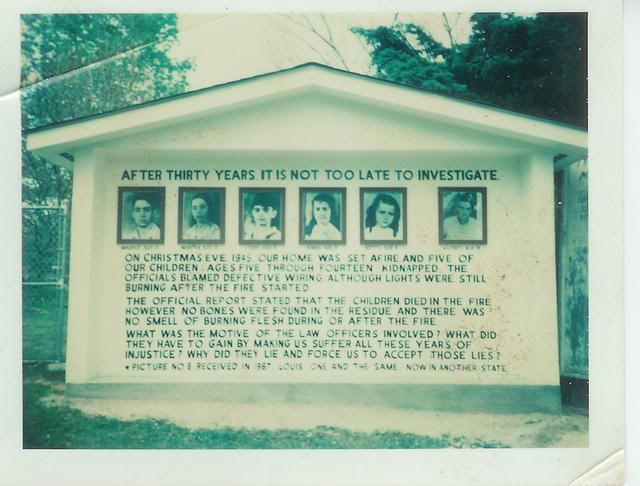

Once outside, Mr. Sodder noticed that Betty, Jennie, Louis, Martha Lee, and Maurice were nowhere to be found. He went to grab the ladder, which was kept near the house, to reach the windows of the room where the children slept. The ladder was missing. Less than forty-five minutes after the fire started, the house was consumed. Firefighters and state police arrived later that morning and placed the cause of the fire on faulty wiring. State police later withdrew their statement. The fire chief and state fire marshal sifted through the ashes and told the Sodders that they couldn’t find any remains. Another report states that the firefighters found a few bones and pieces of internal organs in the ashes, but the family was never told of these findings. Some time after the fire, the fire chief informed the Sodders that he had recovered a body part, probably an organ, from the ashes and buried it in a box on the site. The box was dug up and its contents taken to the funeral home for examination, while a small piece was sent elsewhere for examination. The piece sent off elsewhere was deemed to be beef liver. When the detective went back to the funeral home to find the results of their analysis on the contents he left in their care he was told that they couldn’t be located The acting coroner impaneled a jury of six local citizens who returned a verdict that the five children had died due to suffocation and flames. Within a few months, the Sodders became convinced that their children did not die in the fire. Information began to surface to support their beliefs. An investigation revealed that the telephone line had been cut shortly before or during the fire. A late-night bus driver reported seeing "balls of fire" being tossed upon the roof of the Sodder home. An operator of a motel located halfway between Fayetteville and Charleston reported seeing the children Christmas morning. A Charleston hotel owner reported seeing four of the children in the company of four Italian speaking adults a week later. Three months after the fire, the youngest child found a hard rubber object that was hollow with a twist-off cap. It was identified by Army authorities as an incendiary or napalm bomb called a "pine-apple." It was later discovered that the fire had started on the roof. During the fire, a man was seen stealing a block and chain from the Sodder's garage. He admitted to cutting the "electric line" to the Sodder home. The ladder, which couldn't be found during the fire, was found down an embankment away from the house. A couple of years after the tragedy, Mr. Sodder saw a photo of school children in New York and was certain that Betty was one of the children in the photograph. He drove to Manhattan to see for himself but was never allowed to see the child. Sightings of the children came in from all over the country. Every lead proved fruitless. In 1952, the Sodders purchased a billboard displaying photos of their missing children and offering a reward for the recovery of any or all of the children. The publicity fed rumors that the children had been sold to an orphanage or taken to Italy. The Sodders tried in vain to get their case re-opened, even writing to the FBI. State police and local authorities wouldn’t reactivate the investigation without any evidence of a kidnapping or murder. The investigating fire marshal admitted years later that he did not search through the ashes as thoroughly as he would have liked. Mr. Sodder, initially believing his children had died, bulldozed the site and covered it with four to five feet of dirt, planting flowers in memory of the children. In 1949, Mr. Sodder decided to excavate the site in order to search for human remains. The assistant chief of Naval Ordinance in Charleston and a noted pathologist from Washington, D.C. were among those helping. Four pieces of vertebrae and two small bones that could have come from a child’s hand were located. The pathologist noted that he was amazed at the scarcity of bones recovered after the thorough search, claiming it was unusual that no skulls or pelvic bones were found in a fire that was quick burning and not so intense as to destroy cloth, flooring and other debris found. Back in Washington, D.C., the pathologist determined the bones to be human, having come from a person 14 to 15 years of age. Due to the location where the bones were found within the floor plan of the house, Mr. Sodder didn’t believe the remains to be of his 14-year-old son, Maurice. Another analysis of the bones conducted years later by the Smithsonian Institute determined that the bones came from someone 16 to 22 years of age. It was also noted that the bones bore no evidence of having been subjected to fire. A letter would arrive on a detective’s desk claiming that the bones had been removed from a nearby cemetery and planted at the scene. Many believe the children died that night in the fire and the family was never able to accept the loss. Others believe the children were taken and are still alive somewhere, believing the fire killed their parents and siblings. Mr. Sodder died in 1969, his wife twenty years later. The billboard no longer stands. The youngest of the Sodder children keeps her parents’ quest alive to find out what really happened that night.

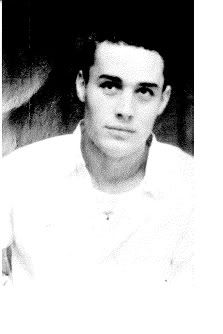

In 1968, over 20 years adter the tragedy, the Sodders received yet another mysterious reminder. An envelope arrived addressed to Mrs. Sodder with no return address. Inside she found only a photograph of a young man, 24-28 years old, wearing white pants and a shirt, and sitting in front of a window. On the back of the photograph were these words: "Louis Sodder" "I love brother Frankie." "ilil Boys" "A90132 or 35" Mrs. Sodder was convinced that the photograph was of her son Louis Sodder, who was supposed to have died in the fire at the age of nine. The Sodders took the photograph to Charleston in an effort to convince Attorney General Donald Robertson to reopen the case. But the Attorney General was not convinced of the identity of the young man. Determined to follow this lead just as they had so many others, the Sodders again employed a private detective. They paid him in advance and sent him to the town which was listed on the postmark of the letter. They never heard from him again. Mrs. Sodder was afraid that if the letter or the name of the town was published it could bring harm to her son. She had no choice but to admit defeat. The photograph was enlarged and placed in a frame in front of her fireplace. She took comfort in the belief that although her children were out of her reach, they were still alive.

On Christmas Eve 1945, a dozen people were asleep in the two-story farmhouse of George and Jennie (sometimes referred to as Jenny or Jeannie) Sodder in Fayetteville, West Virginia: The Sodders and their ten children, ranging in age from 2 to 23. The family had emigrated from their native Italy. George, a sturdy 50-year-old, ran a coal-trucking business out of his home.

When George realized it was too late to do anything, he and his sons joined Jennie and the two girls on the lawn, helplessly watching the house collapse in flames. Five children never emerged from the house. By the time the firetruck arrived, an astonishing seven hours after the local fire department had been summoned, the house was a charred wreck. A small amount of partial human remains were found in the rubble, and that was all. The cause of the fire was later identified as faulty wiring. This verdict has been called into question, however, because the electrical lights on the Sodders' Christmas tree continued to shine even as the fire raged. Later, a telephone repairman concluded that the phone line had been cut rather than burned. This would have occurred very close to the time of the fire, as Jennie had answered a wrong number sometime after 10:00.

The five missing children: Betty (5), Jennie (8), Louis (9), Martha (12), and Maurice (14).

The Sodders, particularly George, grew convinced that the children had been abducted, the fire set to delay discovery. Either he hadn't been told of the remains found by firemen, or he didn't accept that these few, pitiful remnants could really constitute all that was left of the bodies of five healthy children.

One year after the fire, he was certain that a dark-haired little girl in Look magazine was his 5-year-old daughter, Betty. He drove to the girl's school in New York and demanded to see her, but was denied.

Until his death in 1969, George followed similar leads - each one leading to a heartbreaking dead end.

So for over 60 years, the mystery has lingered. The Sodders erected a huge billboard on their property, featuring photos of their five missing children. They offered a $5000 reward for information leading to their whereabouts. This billboard remained standing until after Jennie's death in 1989. Sightings and rumours drifted to Fayetteville from many corners of the world, but no trace of the children has been found.

The mystery thickened when the former fire chief, F.J. Morris, claimed he had buried some of the children's remains on the Sodder property, in a small wooden box. It seems likely he concocted this story to cover up the fact that the remains were not preserved at all, for the box contained nothing but a cow's liver. A fresh cow's liver.

Sources:

- "Mystery of Missing Children Haunts W. Va. Town" by Stacy Horn (audio and transcription). All Things Considered. Dec. 23, 2005. Horn also posted an extensive article on the Sodder case on her blog.

- "Where Are the Children?" by Audrey Stanton. The Register-Herald (Beckley, W. Va.). Dec. 24, 2006.

On Christmas Eve in 1945, the Sodders and nine of their ten children settled in for the evening. Martha, and four of her siblings - Betty, Jennie, Louis and Maurice pleaded to be allowed to stay up and play with their new toys. Mrs. Sodder relented after the children promised to take care of their chores before coming to bed.

Shortly after midnight Mrs. Sodder was awakened by the phone ringing. A female caller asked for a man whose name Mrs. Sodder didn't recognize. The caller gave a weird laugh before hanging up. Dismissing the call as a prank, Mrs. Sodder went to return back to bed but noticed the lights were still on, the shades weren’t drawn and the doors hadn’t been locked. Believing the children forgot to do these things before going to bed, she went back to sleep. She was awakened again by a noise on the roof that sounded "like a rubber ball."

About a half-hour later, smoke began pouring into the bedroom. She yelled for her husband and children. Once outside, Mr. Sodder noticed that Betty, Jennie, Louis, Martha Lee, and Maurice were nowhere to be found. He went to grab the ladder, which was kept near the house, to reach the windows of the room where the children slept. The ladder was missing. Less than forty-five minutes after the fire started, the house was consumed.

Firefighters and state police arrived later that morning and placed the cause of the fire on faulty wiring. State police later withdrew their statement. The fire chief and state fire marshal sifted through the ashes and told the Sodders that they couldn’t find any remains. Another report states that the firefighters found a few bones and pieces of internal organs in the ashes, but the family was never told of these findings. Some time after the fire, the fire chief informed the Sodders that he had recovered a body part, probably an organ, from the ashes and buried it in a box on the site. The box was dug up and its contents taken to the funeral home for examination, while a small piece was sent elsewhere for examination. The piece sent off elsewhere was deemed to be beef liver. When the detective went back to the funeral home to find the results of their analysis on the contents he left in their care he was told that they couldn’t be located The acting coroner impaneled a jury of six local citizens who returned a verdict that the five children had died due to suffocation and flames.

Within a few months, the Sodders became convinced that their children did not die in the fire. Information began to surface to support their beliefs. An investigation revealed that the telephone line had been cut shortly before or during the fire. A late-night bus driver reported seeing "balls of fire" being tossed upon the roof of the Sodder home. An operator of a motel located halfway between Fayetteville and Charleston reported seeing the children Christmas morning. A Charleston hotel owner reported seeing four of the children in the company of four Italian speaking adults a week later. Three months after the fire, the youngest child found a hard rubber object that was hollow with a twist-off cap. It was identified by Army authorities as an incendiary or napalm bomb called a "pine-apple." It was later discovered that the fire had started on the roof. During the fire, a man was seen stealing a block and chain from the Sodder's garage. He admitted to cutting the "electric line" to the Sodder home. The ladder, which couldn't be found during the fire, was found down an embankment away from the house.

A couple of years after the tragedy, Mr. Sodder saw a photo of school children in New York and was certain that Betty was one of the children in the photograph. He drove to Manhattan to see for himself but was never allowed to see the child. Sightings of the children came in from all over the country. Every lead proved fruitless. In 1952, the Sodders purchased a billboard displaying photos of their missing children and offering a reward for the recovery of any or all of the children. The publicity fed rumors that the children had been sold to an orphanage or taken to Italy.

The Sodders tried in vain to get their case re-opened, even writing to the FBI. State police and local authorities wouldn’t reactivate the investigation without any evidence of a kidnapping or murder. The investigating fire marshal admitted years later that he did not search through the ashes as thoroughly as he would have liked. Mr. Sodder, initially believing his children had died, bulldozed the site and covered it with four to five feet of dirt, planting flowers in memory of the children.

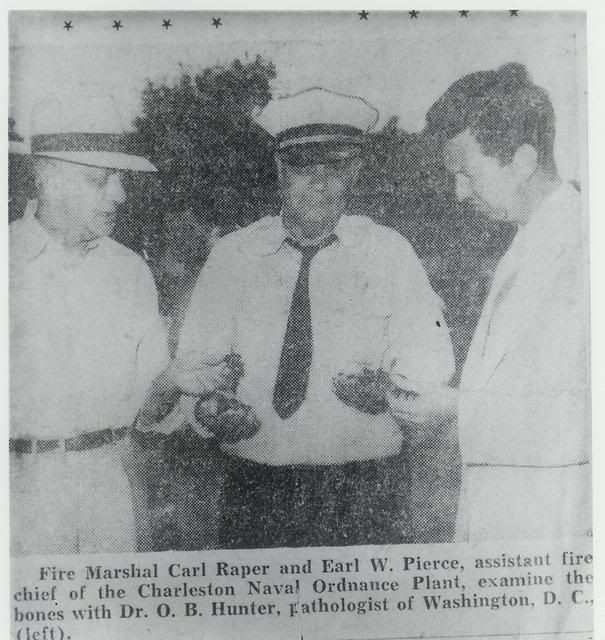

In 1949, Mr. Sodder decided to excavate the site in order to search for human remains. The assistant chief of Naval Ordinance in Charleston and a noted pathologist from Washington, D.C. were among those helping. Four pieces of vertebrae and two small bones that could have come from a child’s hand were located. The pathologist noted that he was amazed at the scarcity of bones recovered after the thorough search, claiming it was unusual that no skulls or pelvic bones were found in a fire that was quick burning and not so intense as to destroy cloth, flooring and other debris found.

Back in Washington, D.C., the pathologist determined the bones to be human, having come from a person 14 to 15 years of age. Due to the location where the bones were found within the floor plan of the house, Mr. Sodder didn’t believe the remains to be of his 14-year-old son, Maurice. Another analysis of the bones conducted years later by the Smithsonian Institute determined that the bones came from someone 16 to 22 years of age. It was also noted that the bones bore no evidence of having been subjected to fire. A letter would arrive on a detective’s desk claiming that the bones had been removed from a nearby cemetery and planted at the scene.

Many believe the children died that night in the fire and the family was never able to accept the loss. Others believe the children were taken and are still alive somewhere, believing the fire killed their parents and siblings. Mr. Sodder died in 1969, his wife twenty years later. The billboard no longer stands. The youngest of the Sodder children keeps her parents’ quest alive to find out what really happened that night.

0 comments:

Post a Comment